The story

It was the comic-style version of The Iliad by Marcia Williams that began my long acquaintance with the (probably) eighth century BC tale. If you click on the link above, you will see the book in question on Amazon. Such versions, from the 2004 film Troy to the influence exerted on the computer game Age of Mythology, show what an impact on popular culture this masterpiece has had. Even if you can’t read Ancient Greek, or even yet if you can’t quite manage the lengthy translation, you will somewhere harbour the knowledge of exactly what happens in The Iliad. At some time in your life, The Iliad has fired your imagination.

Oh my, who could forget the tale of fair Helen, the face that launched a thousand ships? However, if you ask a lot of people, they will tell you that this epic is the story of how the Greeks sacked Troy by using the Trojan horse trick. Close, but no. A more accurate assessment might be how King Agamemnon, leader of the Greeks, took the warrior Achilles’ slave girl, and so Achilles sulked for long enough to get a lot of people killed. He clearly forgot the saying that all’s fair in love and war.

The synopsis tells us:

“The Iliad is the story of a few days’ fighting in the tenth year of the legendary war between the Greeks and the Trojans, which broke out when Paris, son of King Priam of Troy, abducted the fabulously beautiful Helen, wife of King Menelaus of Sparta. After a quarrel between the Greek commander, Agamemnon, and the greatest of the Greek warriors, Achilles, the gods became more closely involved in the action…”

I won’t tell you any more of that. Everyone seems to know the ending of this episode of the Greek invasion, but for those who don’t, I shan’t spoil its conclusion.

Worst bits

Homer’s predilection for listing is the worst habit of the book. He particularly enjoys listing names – one entire chapter is devoted to the soldiers on each ship, and their ancestors. You would be forgiven for taking several chapters to memorize the names of our leading heroes (and the names of their forefathers, as Achilles, for example, is frequently just called ‘son of Peleus’). You would even be excused if you couldn’t immediately work out which side of the war the story is following, since the Greeks are called a whole host of names, including Achaens, Danaans, Argives, the individual names of where they come from… A working knowledge of Greek mythology earned beforehand is recommended. I confess that if I hadn’t liked my myths as a kid, I might have struggled to understand half of what was going on. If you think you’re good with names though, by all means take on The Iliad without prior knowledge.

Characters, without warning, will pause in battle to relay their ancestry, or the origin of their weapons. Of course, no major character is ever killed during these exchanges. Talking at the enemy apparently stuns them into inaction. Overall, it doesn’t matter if you are ultimately killed, as long as you deliver a beautiful speech that wins all the readers over to your side. But you’re still dead, and others begin the disturbing process of fighting over your bare remains.

You may also sigh as the text swings between the believable (the adrenalin of battle) to pure fantasy, and I’m not speaking of the Gods. I believe this tale has frustrated many readers who frown at warriors randomly postponing the war at whim for lavish funerals, and at the way that neither the Trojans nor the Greeks seem to run out of resources, exchanging women and fatted farm animals without batting an eyelid. After all this, you won’t be too astonished to find that you begin to stop caring at each gruesome death, and that you may, in fact, feel some contempt towards the exaggerated mourners.

Major warriors, seemingly invulnerable, bring what appear to be whole battalions to their knees, and the gods randomly dart in and out of the frame of the story to explain away inexplicable personality changes in the warriors. The whole upper ranks are exasperatingly materialistic, enemies and animals are heartlessly slaughtered in sacrifice and all lower ranks are expected to mourn only for the best of their commanders in what might be seen as a shocking disregard for individual humans. Basically, you may begin actively disliking the thoughtless arrogance of self-obsessed principal characters, and that is without taking into account the absolutely baffling intentions and limitations of the gods.

Best bits

It’s hilarious, in that unintended way. Perhaps my favourite moment is when two characters on opposite sides of the battle ask if they somehow know each other. When it is asserted that their families are friends, they then proceed to swap armour. In the middle of battle.

In fact, the ancient Greeks have ‘a thing’ about armour. Achilles is given new armour, and it takes over a page to describe the detail on the shield alone. Warriors will strip dead foes of their armour in the middle of the fight, just casually, and sometimes fight over the naked body afterwards for the right to either bury it, or parade it like a war souvenir. Morals are so very different, hypocrisy is buried in clever rhetoric and no one seems to quite realise how silly they’re all being, getting themselves killed for the sake of the dead. Therefore – hilarious.

Another of my favourite parts – and this could just be me – is the pure gore of the action. Homer doesn’t shy from describing exactly where the point of a weapon falls (though you may giggle at the sheer quantity of times that a spear strikes above the left nipple) nor how brains and intestines splatter out. I was quite surprised to realise how well the ancient Greeks knew their anatomy.

Despite the gratuitous listing, and the battles, perhaps the reason that The Iliad doesn’t sound like a history textbook is its focus on human nature. Kings and Gods alike change their minds, trick one another and throw jibes at their enemies. Love, such a foreign concept to the battlefield, is not only found between warriors and their female slaves and the occasional wife, but also between friends grieving for their lost comrades. Other types of love are found (including a highly suspect paragraph on Boreas and a few horses), but we can all happily ignore those and pretend they never happened.

The gods are simply wonderful, in their symbiotic network, each having to rely on the other; the personification of the hedgehog’s dilemma. They seem almost more human than the mortals, in their childish manipulation, and their casual egoism. They seem at once all-powerful, guiding arrows to take down seasoned soldiers, and at the same time utterly helpless, unable to influence the tide of war or each other. The gods, whether you see them as individuals or as plot devices, show an intricacy of human belief.

Finally, the epic poem contains a wealth of detail, and beautifully figurative language to enjoy. It may promote slightly different ethics to the ones employed today, but it values love and comradeship with a tenderness that is ultimately unexpected.

My book

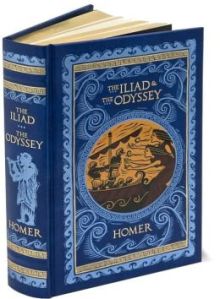

This is the first time I’m reviewing an actual classic for this blog, in the sense of classical literature, and I have an appropriately pretty book to accompany it. That book is the visually lush Barnes and Noble version of the text, also including The Odyssey, and translated by Samuel Butler. The wonderful thing about this edition is that the pages are rimmed with gold, and the text laid out cleanly, like any other fiction novel. The introduction explains a lot about the tale, including the fact that The Iliad is just one in an arc of epic poems, most of which have been lost. Without the essential ‘Principal Personages’ section at the beginning, you could easily forget which god supports which side, and which hero is the son of whom. The Iliad is responsible for 407 pages of this 731 page book, but don’t be daunted by its length. You can’t truly appreciate classical literature, without having read The Iliad.

However, I have been cheating on this lovely copy. I have another version of this, an Oxford World’s Classics version, translated by Robert Fitzgerald, from which I took the blurb that you may read above. You can see its cover to the right. The advantages of this particular edition are the maps of Ancient Greece at its end, and the more comprehensive index of who’s who at its back. Also, this version is advised for anyone looking for a more poetic Iliad as the text is arranged in a style very close to free verse, and occasionally, unlike Barnes and Noble, dips into rhyme. In this book, the story takes 443 pages. The disadvantage is that if, like me, you switch from one book to the other, you may be confused at a few name changes (the Ajaxes of Barnes and Noble become the Aias in the Oxford book, which may seem, to anyone who hasn’t studied Greek, unpronounceable).

Overall

The Iliad is enjoyable. I probably did not appreciate its animal metaphors, or its persuasive passion as much as Homer intended. I grew bored with the lists of names, and descriptions, and I didn’t feel even remotely touched by any of the multiple character deaths. All the same, I loved the culture shocks, and how it brought to life the ancient myths that I grew up with, and laughed with surprise at the bizarre pauses in battles for the weakest of reasons. You may find it funny, or you may find it tedious, but we can’t deny that The Iliad strikes you as the timeless epic that it is.

Hello there! I was looking through some blogs about reading and came across this post about my favorite classical text, the Iliad.

I would first like to say that I have a degree in Art History and Classical Studies so I DO know what I am talking about.

Firstly, the listing aspect is very tedious I am sure, but it has a purpose. The Iliad was originally verbal, it was a story that was sung and it was meant to be a record for Greek people of who was present at the battle. This wasn’t just a story for them, it was their history. The story would have been passed down through generations and the facts needed to have a rhythm to them so they could be properly remembered. The use of titles for each character was another memory aid, such as the “fair skin Athena,” etc. In typical classical studies classes the book that lists all of the ships is often skipped as it is a record and not really something that furthers the narrative story.

That being said, you mention the pauses in the battles annoyed you. Remember again that this is a historical record for these people and these heroes all have their own myths in their right. Certain heroes would have had importance in different areas of the Classical world. This is a place to accumulate them so even if you had no emotional response to their deaths, ancient peoples would have. Also envision these moments in a cinematic way, like a slow motion fight scene. It’s very climactic in that sense.

The best way to enjoy this story is to imagine it as a beautiful flowing song (as was its original state) and the only version of the Iliad I would EVER recommend is the version translated by Robert Fagles. Any other version will taint your experience with the story. Please give it another shot and read that version, it is written in the closest lyrical replication of the original and is beautiful and poetic.

Lastly, appreciate the relationship of Priam with everyone in this story but especially with Achilles. Their conversations are truly what this tale is about, emotion, wisdom and what it means to be human.

This story is absolutely better when read in a class, you can really grow to love and appreciate it. If that isn’t possible, most definitely read up on ancient Greek culture because the things you find funny truly do make sense if you look at it from their point of view.

It is a beautiful and insightful story and I hope you can maybe reread it or simply enjoy it more with a few facts! Good job for giving it a go on your own though, that is a great undertaking!

Thanks for clarifying several aspects on The Iliad for me! As a long lover of Greek mythology, I was aware of many of the aspects that you have mentioned. All the same, I’m mainly reviewing it from an entertainment point of view, in my bid to prove that classics are also able to be enjoyed, as well as studied. From that angle, this poem does not always measure up to the less lyrical modern novel, with its fast-paced action and loose characterisation. However, it’s very true that entertainment was certainly not the only reason that epics were written, and it would be very unfair to forget that.

I really appreciate the fact that you have taken the time to add some background to The Iliad to my blog though. I honestly adore The Iliad, and I think that people like you, who take the time to argue the case for an epic, which is gradually growing under-appreciated, are to be admired.

I have recently found out that I will, in fact, be given a chance to study this great tale, having just received my university lecture list for this year. I cannot express how excited I am!

That’s fantastic! You will get so much more out of a lecture on the story for sure. There is so much more to it than what you can gain from reading it alone. I admit that it probably isn’t an all-readers friendly tale as you definitely need background and culture information to really appreciate what you are reading.

I quite like your blog though and I enjoy what your overall goal is. I’m definitely a fan!

Keep up the work and let me know if you want any more info!

One of my papers for my Greek Lit class explored the artistic merits of these lists. For epics, an audiobook version is essential for a complete experience. As the previous commenter stated, epics are more of an aural art and less of a written one. Even lists have a power when a great orator is reciting them. In fact, the poetic rhythm is strongest in those sections. It almost becomes song. How do you portray the size and power of an army solely through the spoken word? A list is one strategy. It’s weary on paper but spoken in rhythm you gain the sense of ranks upon ranks of soldiers in formation. Because in those days, the scale of the battles and armies was literally unimaginable.

And the interruptions in battle become moments of drama because that is when poetic rhythm is broken to focus on character. It’s also practical because action is harder to follow than speech in recital.

I advise you to listen to Ian McKellen’s rendition of The Odyssey. It’s incredible delivered by a renowned Shakespearean actor. And when I heard Seamus Heaney’s recital of Beowulf, I was almost moved to tears.

The Iliad, or the Odyssey for that matter, are definitely different when read in a class in ancient Greek (as we did at school), nothing at all seems funny, apart from Rhapsody S on Odyssey! But translated I have to admit that it is pretty funny..

I really enjoy your blog!

Reblogged this on Lechaim-To Life : Reflections by Carita Fogde.